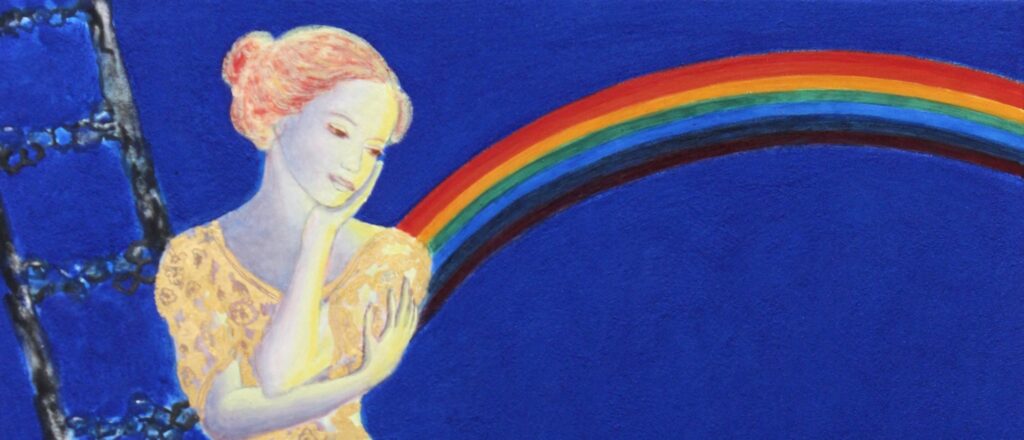

Archetypal images carried within ourselves are just as real – or imaginary – as the physical world we inhabit.

Narrative as a Mirror of Social Concern and Engagement

I would like to comment on my position regarding narrative. The evolution of my painting over the past four decades has focused increasingly on mythological and psychological archetypes which expose and encompass the innumerable facets of the human condition. This developed slowly at first during my thirties and forties as I delved more deeply into the fascinating writings of C. G. Jung and Paul Tillich. Jung’s works, especially “The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche”, “Civilization in Transition”, or “Psychology and Alchemy” helped me grasp the magnitude of our inherited psyche and the limitlessness of our imagination. To summarize, the English sixteenth century poet and writer John Donne perfectly expresses my world view: “We humans are both miracles and catastrophes”.

A selection from exhibitions

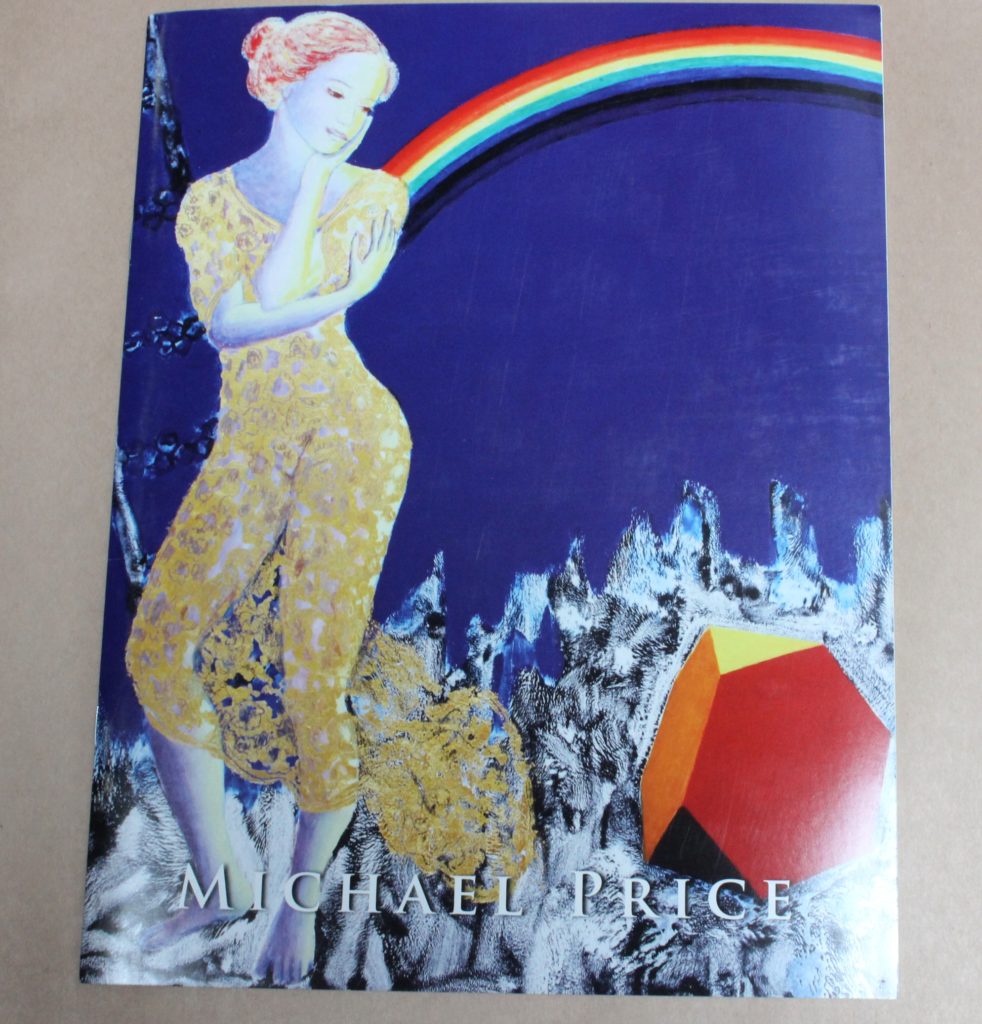

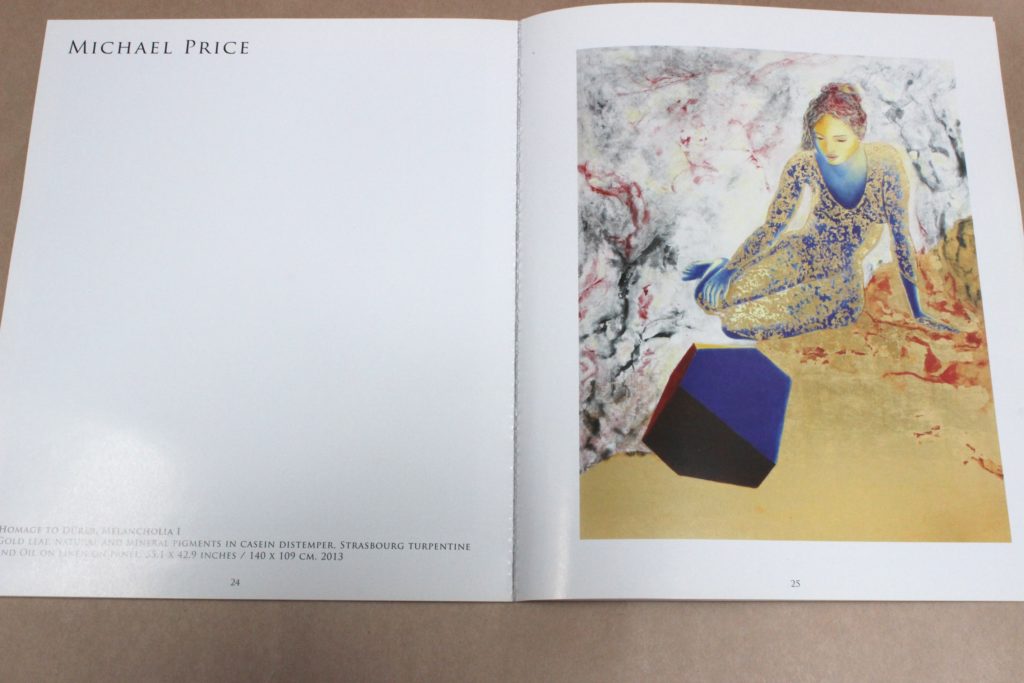

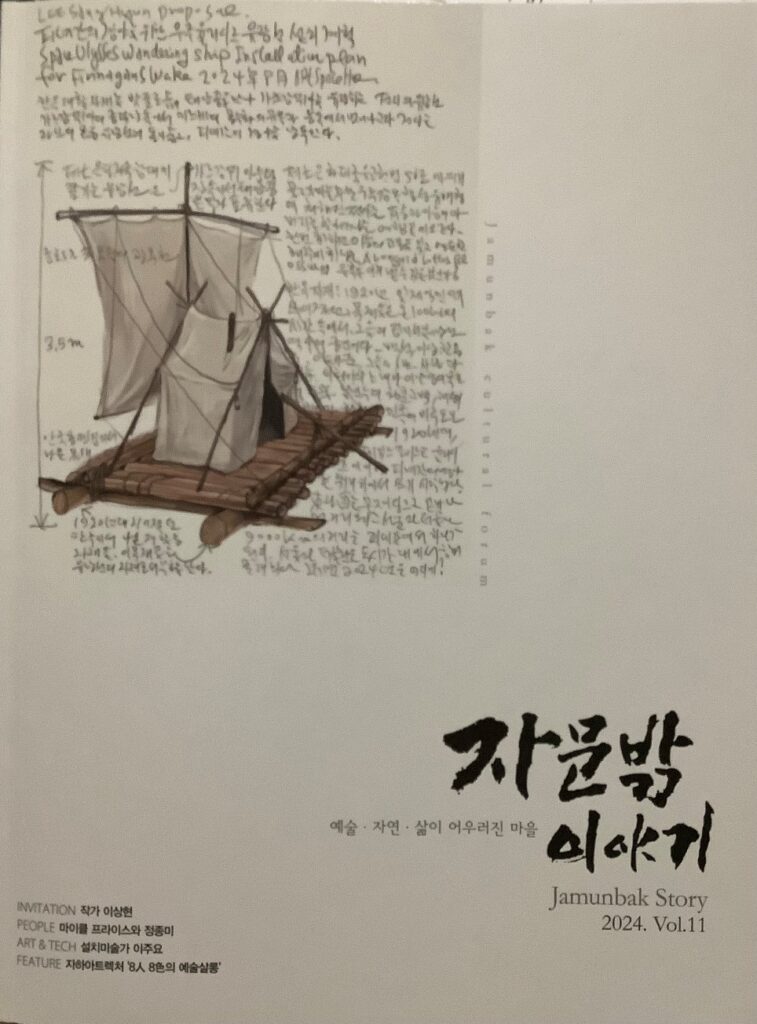

“Clothing the Contemporary Nude in Renaissance Color”

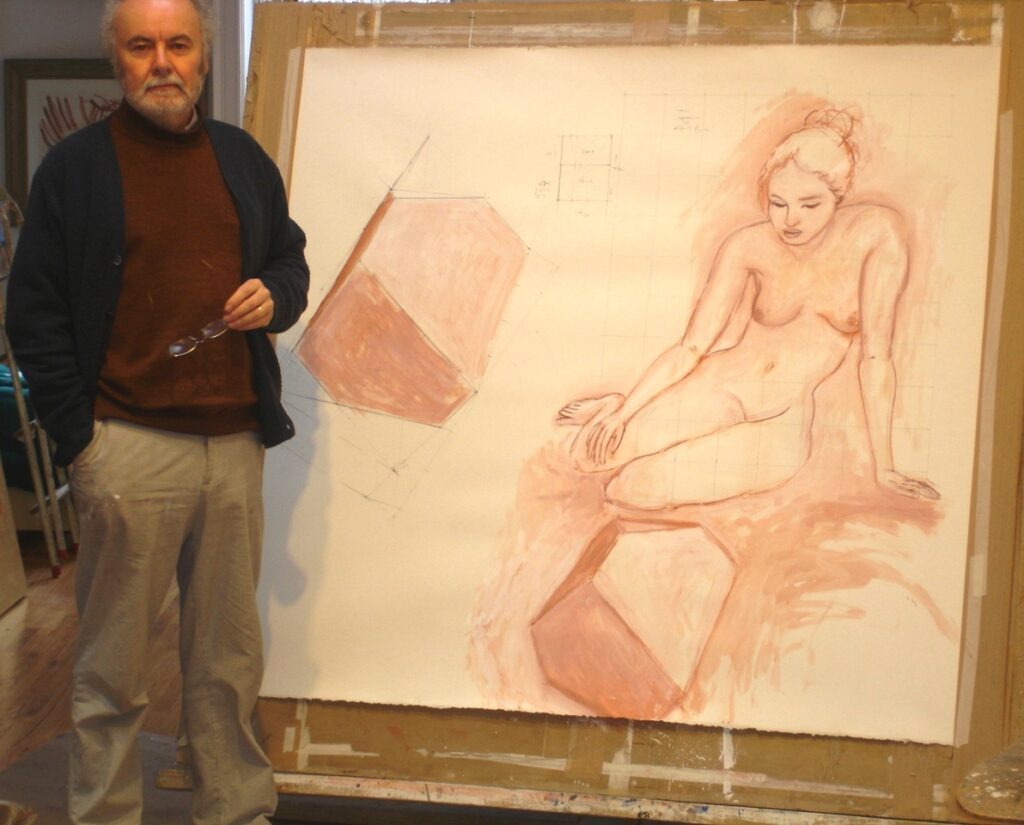

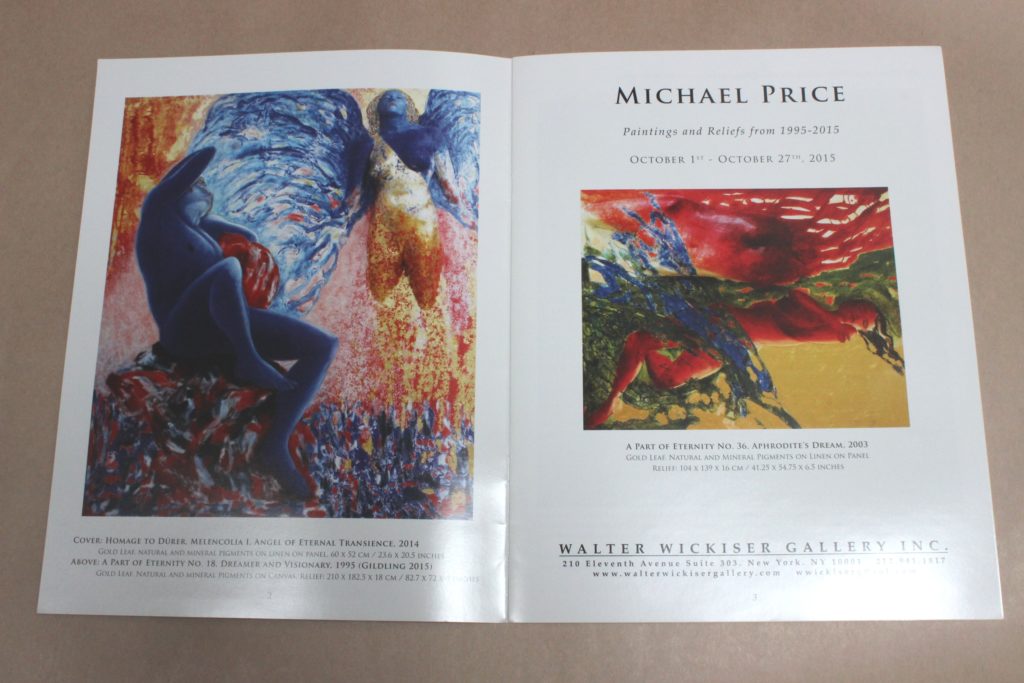

Jonathan Goodman (who has written for Art in America, Sculpture and Art Critical) wrote in 2009, “The proper adjective for Price’s synthesis of opposing colors and forms might well be ‘Dantean,’ so intense are the colors that communicate the composition’s strong feeling. Price returns to the figure on a regular basis, using the nude not only for his historical studies, but as a way of bringing forward representational form in a timeless fashion.”

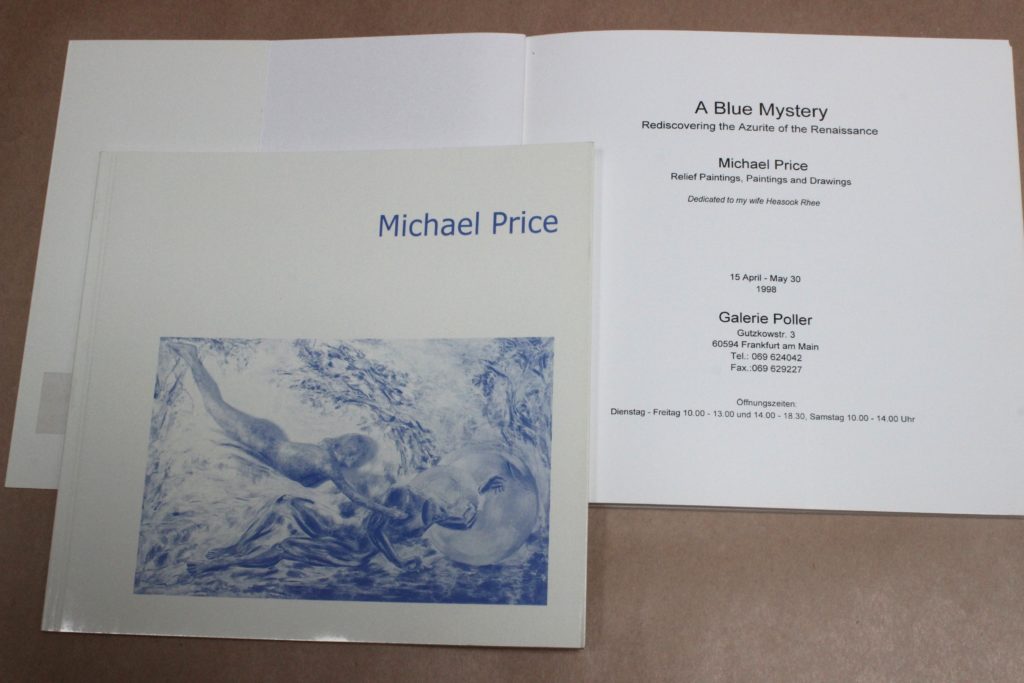

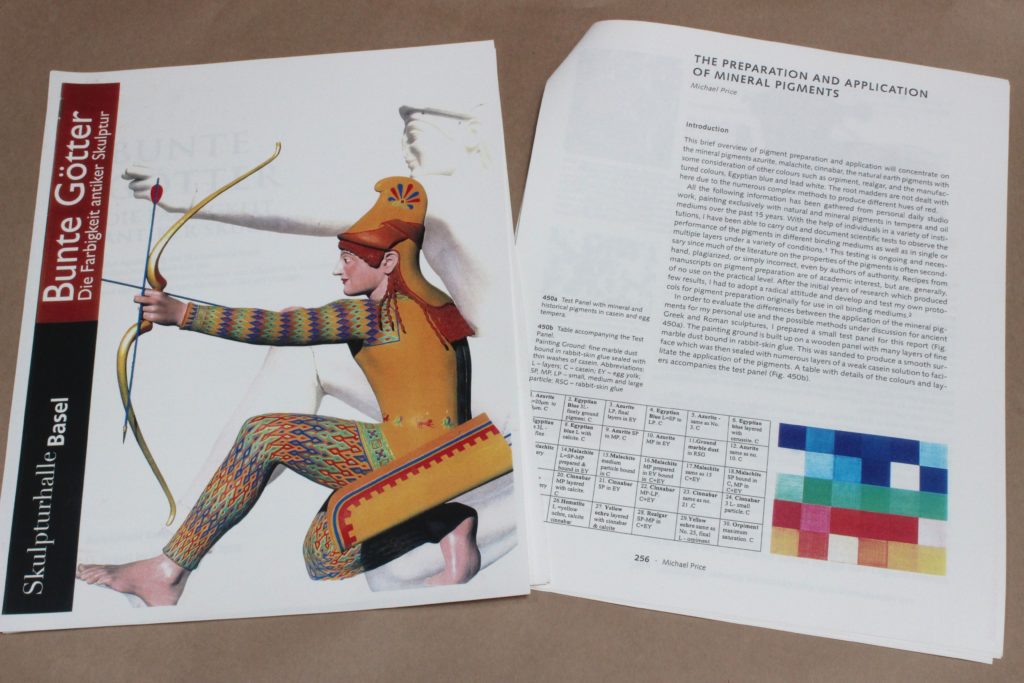

The late James Beck, professor of art history at Columbia University in New York wrote that Michael Price has restored and preserved for Western culture our Renaissance tradition, that depended on artists and their assistants grinding the semiprecious stones and mixing them with a variety of binding mediums according to propriety recipes. Time – and, from my vantage point as an art historian, industrialization – caused the Western culture to irretrievably lose the methods of making natural pigments.

Michael Price has single-handedly mitigated that historic loss.

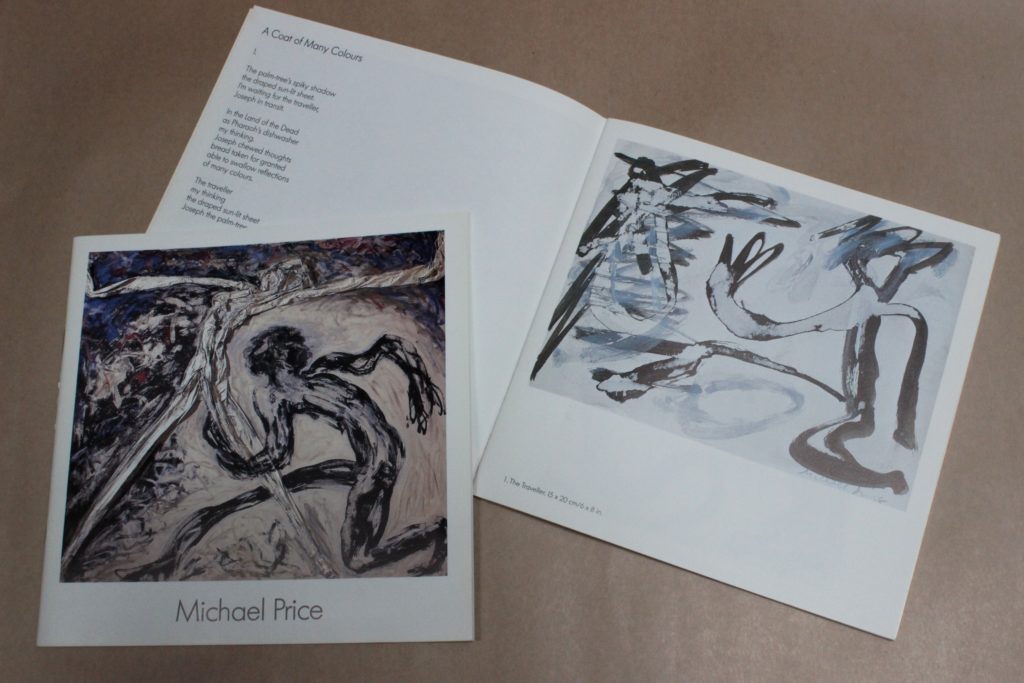

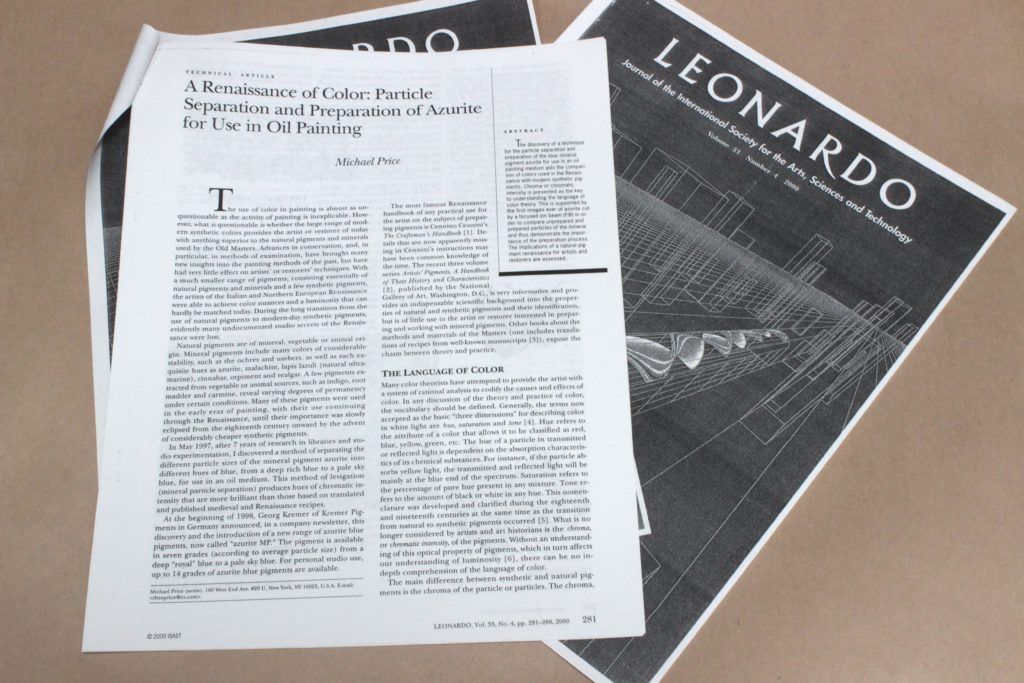

A Selection of Exhibition Catalogues and Published Papers

Biography

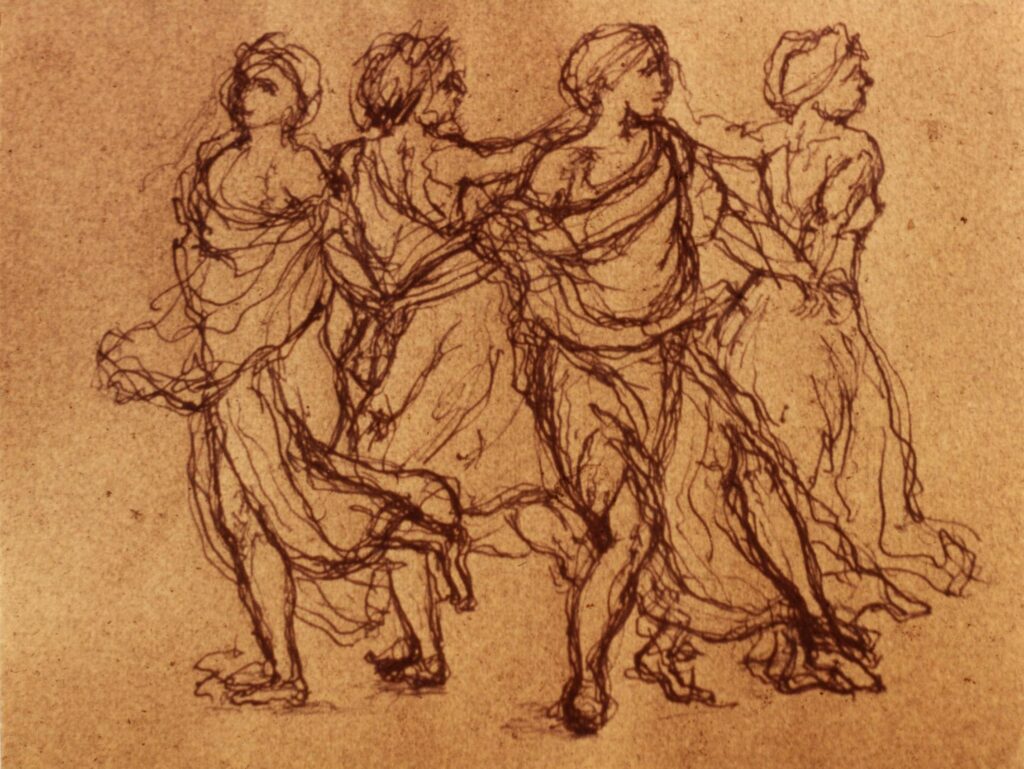

New York artist Michael Price was born in Stoke-on-Trent, England. After school matriculation he studied on a two year foundation course at the local art school and was accepted to the Central School of Art in London (now Central St. Martins). After graduation in 1974, he abandoned the in vogue abstraction of that time based on the conceptualization of the painting process. He received permission to make drawings from the paintings of Nicolas Poussin in the London National Gallery. As one sketch book after another was filled, suddenly art history had become relevant. His focus turned towards Europe. In 1977, he moved to Holland and became fascinated by the paintings of Rogier van der Weyden, Rembrandt and Vermeer. He started to transcribe some of these works into the beginnings of his own language. Then in 1977 he moved to Munich in southern Germany which became his home for the next twenty-two years.

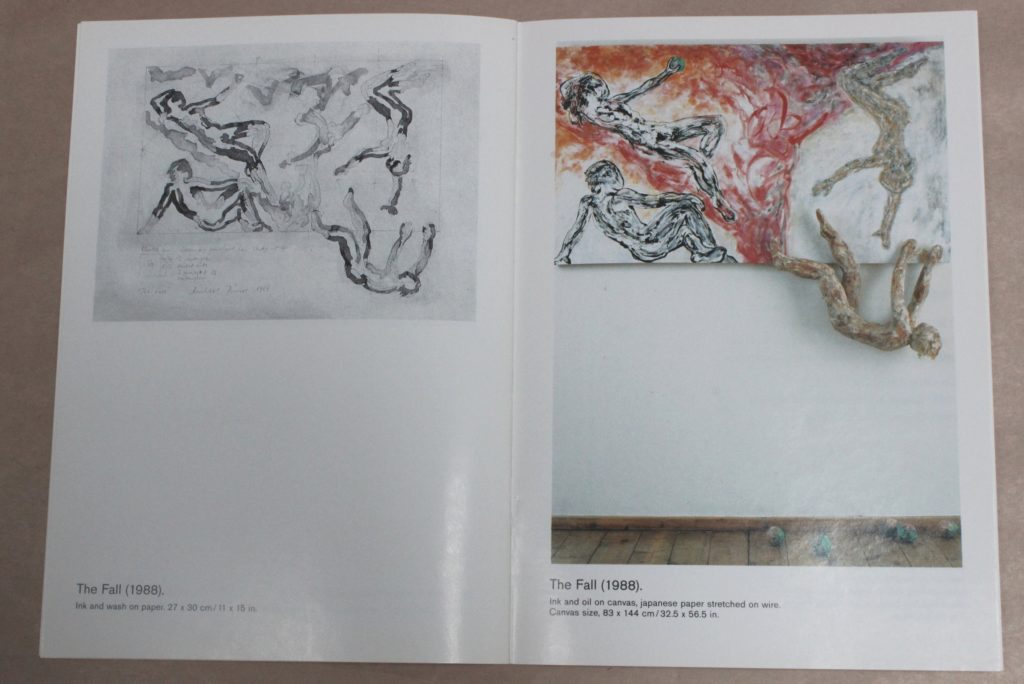

Munich at this time had a lively gallery scene as well as allowing the young artist easy travel by train to museums in Vienna, Florence, Rome and Paris. His first works were accepted into group shows including the famous Munich ‘Haus der Kunst’. This led to his first one-person show in Munich followed by shows in Cologne and Frankfurt. By his early thirties his figurative painting language centred on expressive nudes using Chinese ink and oil paint on canvas. As usual in life, just when everything seems to indicate success, something as simple as a delivery of acrylic gesso, the ground for Chinese ink, no longer functioned leaving brown stains! Fortunately, Munich was home to the Doerner-Institute, a world famous restoration institute which was able to test the ‘gesso’. Through this contact the artist was able to see the restoration of a Tintoretto painting and a paint layer analysis of a Renaissance work under the microscope.

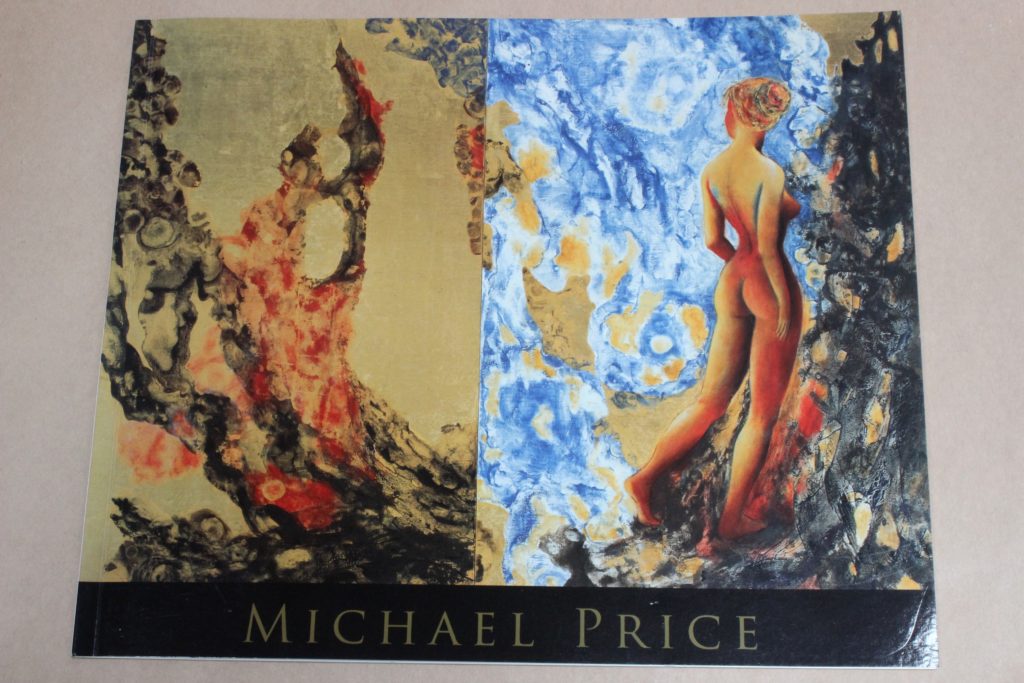

This was the artist’s epiphany with colour. The pigments of the Renaissance were totally different to modern tube paint. At first, the artist thought the change from tube paint to natural mineral pigments from rocks and crystals and natural earths would be simple. He bought four pigments from a shop opposite the museum, ‘Kremer Pigmente’. Azurite, malachite, cinnabar and a lapis lazuli medium quality and he mixed them with either walnut oil for blues and green, and linseed oil for cinnabar red. So voila – following the steps of the Renaissance artists at long last! Unfortunately, the azurite turned grey within two months, the malachite became brownish, the lapis lazuli to grey-black. Only the cinnabar retained its colour. Determined not to give up, the artist started to research conservation literature and after seven years had the first breakthrough with the preparation of azurite and after another three years understood which binding medium could be used with each pigment due to the chemistry of both pigment and binding medium. In 2017, his two volume book “Renaissance Mysteries” was published.

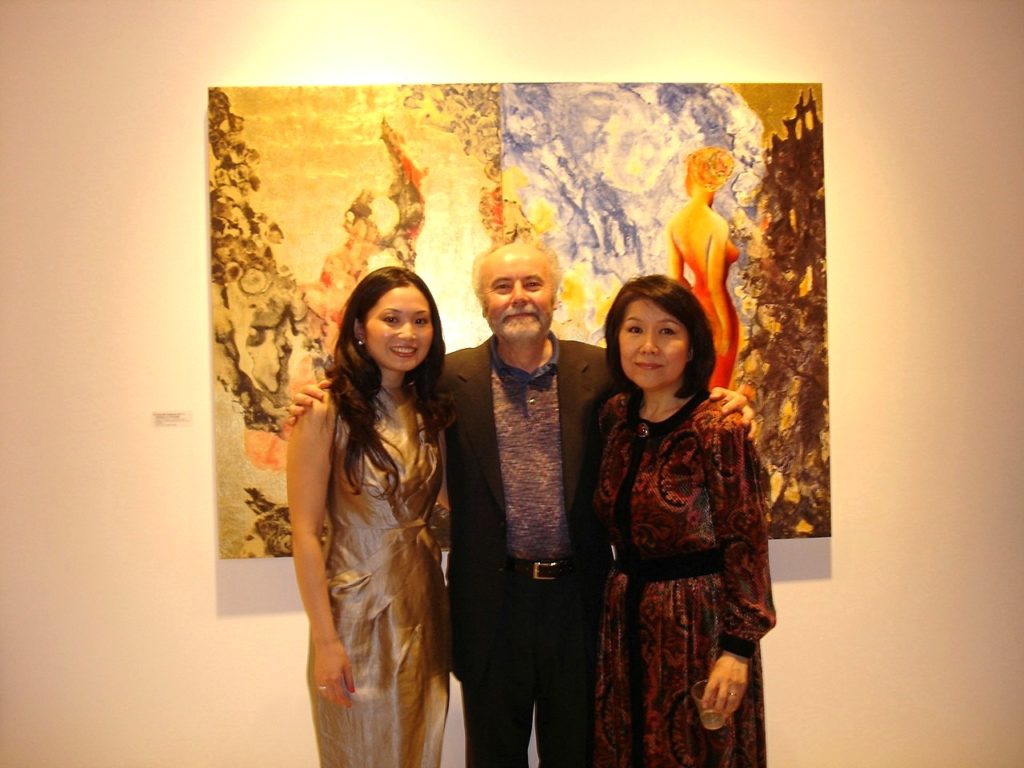

Highlighting both male and female nudes, the artist’s figurative work has focused on the human condition. The main themes explore the mythological and psychological archetypes which expose and encompass the innumerable facets of the human psyche. What does this mean in terms of subject matter? The artist usually works with a series of paintings (usually about ten paintings) to explore a particular narrative. This has included “Evolution of a Myth” (ten paintings). Themes range from “The Birth of Adam” to the surreal world of “Apocalypse, God on Her Bicycle”. “Resurrection Adventures” comprises ten paintings and the most recent series (2024) is “Alchemical Metamorphoses” which explores late medieval European iconography and its evident relationship to the contemporary world’s psychological imbalance (or insanity)! Since 1999, the artist has lived in New York. He has shown regularly in one person and group shows both in New York, New Jersey and Texas. He continues to give lectures on the preparation and application of mineral pigments from rocks and crystals both in the U.S. Germany, China and more recently at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul.

Interview published from the Blog “Artistcloseup.com, October 2021

https://www.artistcloseup.com/blog/full-interview-michael-price

Exhibition

‘The Chromatic Nude’ Artist Michael Price uses natural pigments to paint the human form by Mallory Diefenbach

Link to artsy

through Opulent Art Gallery, London:

https://www.artsy.net/artist/michael-price